Utterly crackers – is the UK registered design system fit for purpose?

We consider whether the UK registered design system is fit for purpose with a recent example concerning the takedown…

An opinion issued by the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Automotive Body Parts Association (“ABPA”) v Ford Global Technologies (“Ford”) this month confirms that US design patents on replacement parts are valid and enforceable. US design patents are the equivalent of UK and European Registered Designs and protect the appearance, rather than the function of products.

The Automotive Body Parts Association originally brought a District Court action in the Eastern District of Michigan (which just happens to include the US automotive heartland of Detroit) against Ford, asserting that design patents related to the Ford F-150 hood (i.e. bonnet) and headlamp assembly were invalid or unenforceable. The ABPA claimed this was because the design patents were directed to body parts that were functional or because an owner that sought to repair their F-150 truck should be allowed to do so without limitation because Ford had already sold the truck (the principle of exhaustion).

The Ford F-150 hood:

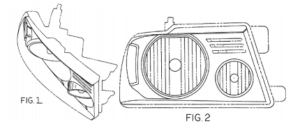

The Ford F-150 headlamp assembly:

Ford did not really have to mount much of a defence in the District Court as the Judge in that instance granted summary judgement in favour of Ford.

“Aesthetic functionality”

The ABPA appealed to the Federal Circuit using the same basic arguments. The ABPA argued that the design patents were directed to body parts that were functional and were invalid. The law in the US is reasonably settled on this point. Previous Federal Court decisions including High Point Design LLC v. Buyers Direct, Inc., 730 F.3d 1301. 1315 (Fed. Cir. 2013) have held that a design patent must claim an “ornamental” design, not one that is “dictated by function.” The Federal Court has also previously recognised that a valid design may contain some functional elements on the basis that an article of manufacture which “necessarily serves a utilitarian purpose” (Sport Dimension, Inc. v. Coleman Co., 820 F.3d 1316, 1320 (Fed. Cir. 2016)). So, the settled law before the ABPA appeal was that a design patent could contain functional elements but not be dictated by function.

Interestingly, the designers of the designs in the design patents are artists, holding Fine Arts degrees from the College for Creative Studies. In a declaration, one designer explained that the designers had “full control and responsibility for the exterior appearance of the … Ford F-150 truck” and that “there were no changes to the aesthetic designs of the parts based on engineering functional requirements.”

The ABPA submitted in the appeal that because consumers seeking replacement parts prefer hoods and headlamps that restore the original appearance of the vehicles, there is a functional benefit to designs that are aesthetically compatible with those vehicles. The ABPA then argued that Ford’s hood and headlamp design is functional because they are aesthetically matched the F-150 truck.

The Federal Circuit court in reply said that no court has applied “aesthetic functionality” to design patents but that the ABPA was asking the Federal Circuit court to become the first to do so, and politely declined. The Federal Circuit court noted that the ABPA had failed to prove that the designs were functional (dictated by function) based on the evidence presented and therefore upheld the District Court’s view that the Ford designs were valid on this point.

Principle of exhaustion

The second point that the ABPA put forward was that Ford’s design patents should be unenforceable against the members all ABPA under the document of exhaustion and repair.

The principal of exhaustion is based on the contention that a patent grants the right to exclude everyone from making, using or selling the thing that is patented but that when the owner of the patent sells the product protected by the patents, the product sold is no longer within the limits of the monopoly. The principal of exhaustion is basically that the authorised sale of the product compensates the patent holder for his invention and that after such a sale, the patent owner can no longer control the use or disposition of the product. The Federal Circuit court cited a number of decisions including Bloomer v. McQuewan, 55 U.S. 539, 549, (1852), United States v. Masonite Corp., 316 U.S. 265, 277–78 (1942), Impression Prods., Inc. v. Lexmark Int’l, Inc., 137 S. Ct. 1523, 1531 (2017), and United States v. Univis Lens Co., 316 U.S. 241, 250 (1942).

In the appeal, Ford actually conceded that when it sells an F-150 truck, its patents are exhausted as to the components actually sold as a part of the truck. The ABPA went further and asserted the sale of the truck not only exhausts any design patents imported in the truck and any individual components actually sold as a part of the truck, but that the sale of the truck as a whole also permitted use of the Ford designs or replacement parts so long as those parts are intended for use with Ford’s trucks. Essentially, the ABPA was submitting that the owner had an unlimited right of repair including in relation to replacement parts.

Again, the Federal Circuit court disagreed with the ABPA. The court said that Ford could have claimed its design applied to the entire truck, but instead chose to protect individual components. Just because Ford had sold the components as a part of an F-150 truck originally, the design patents covering the individual components are not exhausted by the sale of the original vehicle.

The Federal Circuit court decided that just because the components covered by Ford’s patents may require replacement does not compel a special rule in relation to replacement of those components. On that basis the Court said that the designs for Ford’s hood and headlamp were distinct patents and to make use of the designs without Ford’s authorisation is to infringe.

In Europe and the UK, spare parts are eligible for registered design protection but the rights are restricted to some extent by the statutory exceptions for parts of complex products which ‘must match’ other parts of the complex product (e.g. body panels), and products dictated solely by technical function, as well as the ‘repair provision’ in Europe (Article 110 CDR) which states that ‘protection as a Community design shall not exist for a design which constitutes a component part of a complex product used within the meaning of Article 19(1) for the purpose of the repair of that complex product so as to restore its original appearance’.

Over the years since its introduction, the ‘repair provision’ in Europe has been tested in relation to allow wheels, where copies were held to infringe, with the court stating that the manufacturer of the spare part must show an ‘objective necessity’ to imitate the original part and the exception only applies where a manufacturer produces a replacement part for the purpose of repair of the complex product. Additionally, the narrowness of the exclusion for products dictated solely by technical function has been confirmed by the courts, requiring, in short, that no aesthetic consideration has been given by the designer to the visual appearance of the design in question.

The outcome of the appeal enforces the position that US design patents can be used by manufacturers to protect the aesthetic design of parts of their vehicles. A design patent and corresponding registered designs outside USA can be an important tool allowing the manufacturer to protect what is often a significant investment in design of a product, particularly where the aesthetics of the product are important.

All in all, the decision is a resounding endorsement of the use of design patents in the automotive industry in the US in particular but also in the protection of ornamental designs for products generally.

The original US decision can be found here.

If you would like advice on seeking design protection, please get in touch to speak to one of our design experts.