Webinar: A practical guide to reviewing and auditing trade mark portfolios

Join our upcoming webinar on reviewing and auditing trade mark portfolios on 19th March 2026.

The ruling, similarly to Nestle’s unsuccessful appeal earlier this year to register the 3-D shape of their 4-finger KitKat chocolate bar as a trade mark, demonstrates the difficulties of registering and enforcing rights in 3-D shapes.

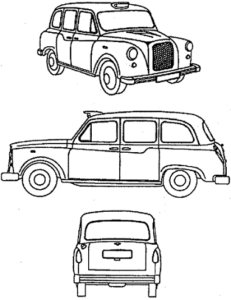

This case concerns an appeal by The London Taxi Corporation Limited t/a The London Taxi Company (‘LTC’) against the 2016 High Court decision where (amongst other things) it was held that LTC’s EU and UK trade mark registrations for the 3-D shape of its London taxi were invalid, as they lacked both inherent and acquired distinctive character. The case came about as a result of LTC bringing an action for infringement and passing-off against Frazer-Nash Research Limited (‘FNR’) claiming that FNR’s ‘Metrocab’ (pictured below) was deliberately created to resemble its traditional London hackney carriages.

The trade mark registrations relied on by LTC in the proceedings are as follows:

1. EUTM No. 951871, covering ‘motor vehicles, accessories for motor vehicles; parts and fittings for the aforesaid’ in class 12.

The Court of Appeal dismissed LTC’s appeal.

Probably the most significant outcome of the Court of Appeal decision was the upholding that LTC’s registered trade marks for the 3-D shapes of its London hackney carriages lacked both inherent and acquired distinctive character and were therefore invalid.

It is settled that, when considering 3-D marks depicting the shape of a product, it must be taken into account that the average consumer will not necessarily perceive such marks in the same way as they would a word or figurative mark which is not related to the appearance of the product(s) it is used on. Without the presence of a graphic and/or word element, average consumers do not really make assumptions about the origin of a product on the basis of its shape alone or the shape of its packaging alone. It is therefore more difficult to establish distinctive character in relation to 3-D marks than it is for word or figurative marks. Only a 3-D shape mark which ‘departs significantly from the norm or customs’ of the sector in which it is used can fulfil its essential function as a badge of origin and therefore possess distinctive character.

In this case, when considering whether the marks relied on by LTC departed significantly from the norms and customs of the sector, the court broadly interpreted the relevant sector. It was not to be limited only to London licensed taxi cabs, but the car sector in general, which included models in production at the date of the application, models on the road and models which the average consumer could be expected to have seen.

When LTC’s marks were compared with the basic design features of the car sector (e.g. ‘superstructures carried on four wheels, the superstructure having a bonnet, headlamps and sidelights or parking lights, a front grille’ etc.), the court determined that the features were merely variants on the standard design features of a car.

‘It is obvious that none of the LTC features is so different to anything which had gone before that it could be described as departing significantly from the norms and customs of the sector’.

Therefore, it was held that the trial judge was right to hold that the marks did not have inherent distinctive character.

It was also held that the trial judge was correct to hold that the marks did not possess acquired distinctive character.

As the average consumer (in this case it was held to include the hirer of a taxi – see point 3 below) is not used to the shape of a product being used as a badge of origin, their focus would be on the provider of the services being supplied (i.e. the taxi driver), rather than on the manufacturer of the vehicle they are travelling in. The evidence supplied by LTC (adverts on flip-up seats in the taxis which advertised the name of the manufacturer) was not adequate enough to establish that consumers perceived the shape of LTC’s taxis as originating only from LTC and no other manufacturer. The KitKat case considered, there must be evidence from which it can be deduced that a consumer understands there is only one manufacturer of products of that shape. Therefore, it was not shown that the marks had acquired distinctive character.

As alluded to above, it was held that the average consumer includes any class of consumer to whom the guarantee of origin is directed and who would be likely to rely on it (e.g. when making a decision to buy or use the goods/services). It does not matter whether this is someone who possesses the goods or someone who merely hires the goods. It was therefore held that both the owners of the taxis and the hirers of the taxis were to be considered as average consumers for the purposes of deciding whether or not the marks relied on by LTC had inherent or acquired distinctive character.

The Court of Appeal also ruled on other issues regarding infringement and passing-off, substantial value, revocation for non-use and the defence of honest practices. However, considering that the trade mark registrations relied on by LTC were declared invalid, these were moot points and shall therefore not be discussed here.

This case is yet another example of trade mark owners facing difficulties in the UK in protecting and enforcing shapes as trade marks. This is because, as clearly highlighted by the present case, shapes are not generally perceived as indicating the origin of goods and/or services, which is the primary function of a trade mark.

In order to assess distinctiveness and whether a mark indicates the origin of goods/services, as set out by the Court of Appeal in the present case, it is important to consider the sector in which the mark is used, what the customs and norms of that sector are and whether the mark departs significantly from those sector norms.

In some circumstances, it may be the case that seeking a registered design for the shape of goods will confer more adequate and enforceable protection. It may well be desirable to try and obtain registered trade mark protection for the shape of goods, as this will confer a monopoly on that shape in perpetuity (as opposed to a monopoly for a limited amount of time of 25 years for a design). However, if the trade mark registration is not valid, trying to protect the shape of goods in this way will have no value.

In the present case, LTC will now have the option to appeal further to the Supreme Court and therefore the dispute may continue. We will continue to monitor this matter and report any further developments.