UPC Update: Germany ratifies the UPC Agreement

The official start of the Unified Patent Court system will therefore be 1 June 2023.

The Unitary Patent (UP) system is a relatively new European patent system which came into effect on 1 June 2023.

Therefore, we have compiled a list of things you need to know about this new system, and issues you will need to consider. Further information can be found in the FAQs on the UPC website.

The changes affect what happens after a patent is granted. The UP makes it possible to enforce or attack European patents in a single action across all the countries within the UPC system. However, the existing nine-month opposition period for oppositions at the EPO remains; and any pending opposition proceedings before the EPO will not protect patents from a second attack before the UPC.

The UPC thus has jurisdiction to enforce and/or invalidate any EP patent with effect for all participating UPC states.

As with European Community trade marks and designs, a UP is a single right across all UPC states. A UP cannot be owned by different parties in different UPC states, and it is not possible to abandon the UP in some states only. However, the patent can be licensed for individual UP states and to different licensees.

It is possible to validate and renew a UP in all UPC states by submitting one translation of the whole patent and paying a single fee to the EPO.

To get a UP, the application procedure is still carried out by the EPO in the same way as at present, and after grant, you can choose for the European patent to become a UP to cover the participating states.

A conventional European patent is still needed to cover non-UPC states. Validation and renewals in non-UPC EU states (including Spain, Poland, Croatia) and non-EU states (e.g. UK, Switzerland, Turkey) will continue as before.

IMPORTANTLY, however, existing conventional European patents and patents granted in the next few years will fall under the dual jurisdiction of the UPC and national courts, unless the patentee opts out the patents from the jurisdiction of the UPC. if a patent is not opted out, it is possible to litigate the European patent before the UPC or in the national courts. This has its pros and cons, which is discussed in more detail below.

Not all European countries are involved. Currently, the position is:

18 countries are in: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Sweden.

UPs filed now will have effect in all of these countries. Likewise the UPC has jurisdiction in these countries for all non-opted out European patents.

6 countries intend to join but haven’t yet: Cyprus, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Slovakia.

UPs granted before ratification by these countries will not have effect there.

As countries join the UPC, they will automatically be included in any UP pursued after they join, but the territory of a UP is set by the grant date, so individual UPs will not expand in territory as new countries join.

NOT participating in the UPC are the following EU Member States: Spain, Poland, Croatia, as well as the non-EU EPC states: Iceland, Norway, Turkey, Switzerland, Serbia, Albania, Macedonia, and the UK.

Importantly, the UPC is not compulsory. However, the default position is that everything is opted in, so all current European patents (i.e. so-called “bundle” patents) automatically fall under UPC jurisdiction, unless they have been opted out. The UPC thus has jurisdiction to enforce and/or invalidate any EP patent with effect for all participating UPC states. This applies to all European bundle patents, including those already granted and still in force.

UPs, however, CANNOT be opted out.

There are thus two options if you validate your patent as a so-called “bundle” patent (covering UP states individually, not with a Unitary Patent):

Option (i) allows you to start European enforcement actions early and potentially shape early case law. However, this option could be risky for high value patents which would be open to central attack.

Option (ii) allows you to avoid central revocation.

There is no official fee for opting out. An opt-out will last for the lifetime of the patent, unless the opt-out is withdrawn.

It is possible to withdraw an opt out and opt a patent back into the UPC, but only as long as there is no national litigation involving the patent. As such, a competitor can prevent you from opting in by attacking your patent in a national court. Moreover, withdrawing the opt-out is a one-way ticket; it will not be possible to opt back out a second time.

Being part of the UPC may be a useful tool if you opted out but later wanted to try and enforce a patent across a number of European countries in a single action.

However, if a non-opted-out European patent is litigated in the UPC system, then it cannot be opted out in the future. Conversely, if any designation of an opted-out European patent is litigated in the national courts it cannot then be opted back into the UPC system.

Therefore, being in the UPC system may be advantageous for some patents, but not for others.

There is a transitional period of 7 years (which may be extended for a further 7 years) within which an opt-out can be filed. The opt-out will however not be possible if proceedings before the UPC have already begun against the patent. It is thus important for you to opt out any patents that they do not want to be part of the UPC court system as soon as possible to avoid being forced into UPC proceedings by a central revocation action. We therefore recommend opting out a European patent around the time that it is allowed (or earlier).

Once the transitional period ends, the opt-out will no longer be available.

Additionally, during this transitional period, for ‘opted-in’ patents, there will be the choice of whether to bring an action relating to a European patent before a national court or before the UPC. If a patent is in the UPC system once the transitional period ends, any proceedings must be brought before the UPC.

For patents granted under the UPC as a unitary patent, the possibility of opting out or bringing an action before a national court during the transitional period will not be available.

After the transitional period, European patent applications and conventional European patents which have not been opted out will be litigated exclusively before the UPC in the same way as European patents with unitary effect, as with all new applications filed after the transitional period ends. The only way then to avoid the UPC’s jurisdiction then would be to file national applications in Europe.

Wilson Gunn can advise on the procedures involved in opting a European patent in or out of the UPC, as well as for requesting a Unitary Patent.

You will need to decide whether or not to have your European patents and applications within the UPC system or not.

Strategically, some patents and applications may be better off in the UPC system, while others may be better served staying out. Therefore, we have compiled a list of the key advantages and disadvantages of the UPC which may factor into any decision-making.

Potential advantages of the UPC

Black applies in all cases; red applies only if you are in the UPC with a Unitary patent (not a bundle patent that’s not opted out).

Potential disadvantages of the UPC

Black applies in all cases; red applies only if you are in the UPC with a Unitary patent (not a bundle patent that’s not opted out).

It should also be considered that while a patentee can initiate infringement proceedings before the UPC, this also opens the patent to a central invalidity attack and noninfringement counterclaims in the UPC.

Also, competitors can trap opted out patents permanently outside the UPC’s jurisdiction by initiating a lawsuit in a national jurisdiction, which could effectively decrease the value of those patents.

The main issues to consider in relation to potentially opting-out and avoiding the UP system altogether are:

(i) The strength of the patents

A weaker patent will obviously be more vulnerable to challenge. Not having it exposed to potential central revocation across all states in one action would therefore be preferable. This could apply, for example, to patents where the granted claims are rather broad, especially if they are broader than other related cases due to prior art which was not considered by the EPO. Such patents may be better off opted-out.

Conversely, a patent perceived to be stronger should be more robust under challenge, so the UPC system would be less of a threat, and the ability to enforce it Europe-wide in a single action may be preferable.

(ii) The value of the technology covered by each patent to the business

It may be preferable to shield patents which are highly valuable to your business from any UPC central attack, so any challenge and potential revocation would have to be individually before the national courts in each of the validated states. Also, in some cases, it may also be worth assessing how your various patents may interact to protect their commercial products.

You should link your patents to their products and assess the importance of those products to the business. For example, if any particular patent covers a successful product, or is bringing in money via Patent Box, then you may wish to opt it out.

(iii) The likelihood of enforcement in different countries

If you were anticipating enforcing a patent in different countries, then central proceedings would be more cost effective. Remaining opted in (or opting back in) may be a preferable option here. Bear in mind, of course, that often matters are settled in pre-action correspondence, without action at any court, let alone several.

(iv) The likelihood that a third party will attack the validity of the patents

If the likelihood of a challenge to the patent is perceived to be high, then you may wish to opt out to avoid central attack.

If the likelihood of a challenge is perceived to be low, and the patent is considered low risk, then you may not be as inclined to opt out.

(v) Costs

Where might you want to validate your patents? If it would be in only a low number of states – e.g. UK, FR, DE – then the UPC is not cost-effective, especially as the UP will not cover the UK. However, if validation in many states would be desired, then the UPC is more cost-effective.

Alternatively, the relatively low cost of getting protection in all UPC states rather than 3 or 4 for not much more money may make the UPC more appealing.

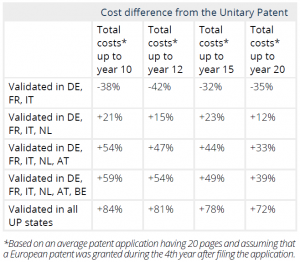

In terms of potential cost effectiveness or otherwise of the UP system, the estimated cost differences between validating in different countries separately and having a UP, over different durations of the patent and for validation in different states could be approximately:

The opt-out must be filed either by the actual owner of the patent or their representative.

The opt-out request must be filed in the name of the correct proprietor. If not done correctly, an opt-out could be deemed invalid, leaving the patent still open to challenge under the UPC system.

If the actual owner (or owners) in respect of any of the UP states differs from the registered proprietor as listed on the EPO register, the parties filing the request will need to be able to demonstrate chain of title from the original/registered rights holder to themselves, so any challenge to the validity of the opt out can be rebutted.

Other issues

There are also other issues to consider in relation to the UPC:

(i) What happens when your patents have joint ownership?

Who has the right to opt a jointly owned patent out of (or into) the UPC system?

While any existing collaboration agreements may define which party has the right to direct patent prosecution and commence infringement proceedings, it is unlikely that existing agreements will include any clauses relating the UPC.

In such cases, the owners will need to be in agreement to file an opt-out request. Patentees with joint-owned cases will thus need to seek the consent of the other co-owner(s), and time would need to be allowed to obtain this.

Also, it is suggested that all future such collaboration agreements should include clauses relating to the UPC.

(ii) Does it matter which co-owner is named first on the patent?

Yes, if they are of different European nationalities or have different places of business within the participating UP states. The nationality or place of business of the patentee determines which national law applies to the patent as an item of property. If a UP has joint owners with different European nationalities within the participating UP states, the law of the country of the owner named first on the application as filed will apply.

If there are no owners within the participating UP states, German law applies.

(iii) What happens when a patent has an exclusive licensee?

Exclusive (and non-exclusive) licensees will not be able to apply for an opt-out of any patent they license.

However, a patentee may want to consider the wishes of the licensee when deciding whether to opt-out or not, or even allow the licensee to make the decision. If the former, it would have to be determined who decides if they don’t agree. If the latter, should a licensee be able to do so without the licensor’s consent, given that the licensor may not want to have proceedings in the national courts? It would also have to be determined who was responsible for any extra costs incurred in opting in or out; or for defending against invalidity attacks in the national courts following any opt-out.

Additionally, if a patent is exclusively licensed to different companies in different countries, each licensee would likely be able to bring infringement proceedings in their respective countries under the terms of the license agreements. If the patent is not opted-out, one licensee could initiate infringement proceedings before the UPC and thus block the opt-out before any opt-out is registered, as well as potentially provoke a central revocation action at the UPC, which could potentially lead to the loss of patent rights for the other licensees in their countries.

Conversely, if the patent is opted-out, one licensee could initiate infringement proceedings before the national courts, and thus prevent the patent from ever being opted in. Some central control of the licensees’ ability to litigate would thus be required.

These are the sort of issues which a licensor would need to address with their licensees. New licences should be drafted so that they make clear who has the right to opt out, and who has control of any potential litigation strategies.

(iv) Future filing strategies

You may want to have a different filing strategy going forward, potentially filing a mixture of EPs and national applications to give the potential for different modes of enforcement. However, this is a longer-term issue, only becoming relevant after the transitional period ends.

Essentially, the main issue is to decide what to do when European patents grant, namely when to choose:

(i) UP;

(ii) Opted out bundle; or

(iii) Opted in bundle.

Which option best suits you will need to be determined on a case-by-case basis, unless you were to establish a policy to treat every case the same way.

Overall, for many UK based patentees, the UK’s withdrawal may be the best of both worlds, allowing them to have a UK patent in their home market and a single patent for the rest of the UP states. Formerly, having the patent in your home market subject to the decisions of a brand new court elsewhere could have been seen as a large downside; however, on account of the UK’s non-participation, at least the UK patent is safe from central attack at the UPC, so the UP may be much more attractive than it was – after all, wherever it would have been litigated would have been outside your home market.

(v) Monitoring competitor patents

If a relevant patent of a competitor’ is part of the UPC system and has not been opted out, then if considering revocation, thought should be given as to whether to initiate central revocation proceedings.

For advice on your options regarding the UPC, please get in touch with us or speak to your usual Wilson Gunn contact.

Further information can also be found in the FAQs on the European Patent Office website.