European Patent Office signature decision

A recent decision of the President of the EPO issued on 9 February 2024 appears to signal a departure…

Bruce Willis’s character John McClane put it fairly eloquently (although using much more colourful language) in the 1988 film, Die Hard, when he said (amongst other things ‘if you’re not a part of the solution, you’re a part of the problem’.)

Although 3D printing began to move from science fiction to reality in the mid-1980s, it really became popular in the 2000s. By the early 2010s, the term 3D printing, rather than additive manufacturing (AM), was being used as an umbrella term for any processes in which material is deposited, joined or solidified under computer control to create a three-dimensional object, usually layer by layer. Additive manufacturing is now arguably a broader term which encompasses 3D printing.

When 3D printing surged in popularity in the mid to late 2000s, many intellectual property experts surmised that the proliferation of such a low-cost manufacturing device would result in more infringement of intellectual property, simply because anyone with access to a 3D printer and a CAD file of a product could potentially reproduce that product by using 3D printing technology.

Whilst there are many more actions that need to be considered when it comes to the infringement of IP over and above 3D printing of the end product (for example, does creation and dissemination of a computer file used to print a protected product infringe?), the thinking about whether 3D printing is a contributor of the ‘problem’ of IP rather than a part of a solution seems to be changing.

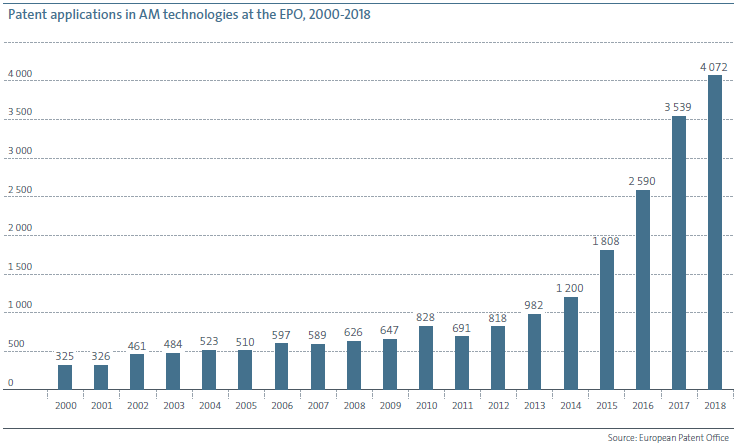

A recently released study by the European Patent Office (EPO) has found that:

This growth rate is more than ten times faster than the average yearly growth of patent applications at the EPO in the same period (3.5%).

In a direct excerpt from the report

New industrial applications of AM technologies account for the largest share of patent applications in AM so far (50%). Other patent applications are related to machines and processes (38%), innovation in materials (26%), and digital technologies (11%). Almost 23% of AM patent applications relate to two or more of these different technology sectors.

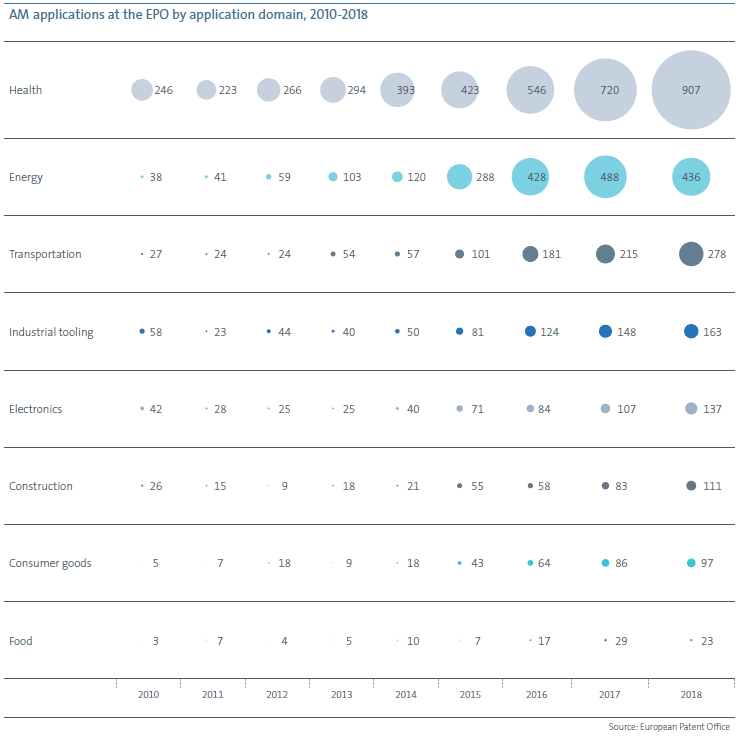

In a further breakdown of the numbers, the use of AM in the medical and health sectors has generated the largest number of patent applications (in the AM field) since 2010.

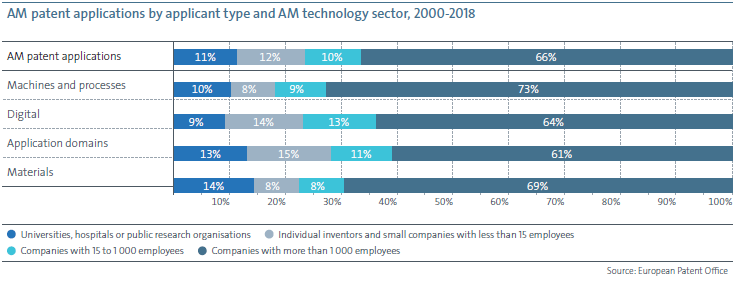

Furthermore, while two out of three patent applications in AM technologies were filed by very large companies, companies with less than 1000 employees accounted for 22% of applications. Individual inventors and small businesses with less than 15 employees generated a very healthy 12% of patent applications in AM between 2000-2018 as the chart below shows (which also shows the breakup by technology sector):

So, given the dramatic increase in the number of patent applications being filed for AM related technology, the question is: is AM, seen ten years ago as one of the largest challenges facing the intellectual property field and the owners of IP, still a part of the problem or is it becoming a part of the solution?

The question is perhaps most clearly answered in the closing paragraph of the Introduction to the report which reads in full:

The rise of AM is also set to have a profound economic impact on supply chains and business models in the years to come. AM streamlines and expedites the product development process, since most parts can be developed and quickly iterated in the digital world. While originally used for prototyping, its value is now seen in making industrial manufacturing more efficient, by using fewer resources while making it easier and cheaper to build complex shapes, geometric features and custom one-off designs (WEF, 2020). As the technology matures, it has the potential to redesign entire industry value chains, with further impact on the price of goods, consumer experiences and labour market conditions. The rise of AM will then oblige companies to rethink their distribution models and to adapt to new forms of competition, while facing the challenge of creating appropriate legal frameworks to safeguard competition.

So, it may be that the focus on AM has shifted from one in which AM is a source of possible infringement of rights to a technology that makes it easier to create new products because of the ease of manufacturing. It can lower entry costs for new products and as the quality of the 3D manufacturing continues to increase, it will likely move from a prototyping tool to a fully-fledged manufacturing option.

The question therefore, as with most things, has a balanced answer in that whilst it does create an opportunity for use to infringe IP rights, it also creates an opportunity for new thoughts, directions and products that may have not been commercially possible before the mainstream acceptance of AM. As with the world in general, there is no black and white answer, only shades of grey.

It will probably be a matter whether a business chooses to be an infringer or to use AM to create new opportunities, but at least some businesses are looking at it as an opportunity and definitely taking steps to carve out their own niche.

Given that the UK is already the second largest European contributor to additive manufacturing innovation behind Germany, what is clear is that more innovative UK businesses are choosing to protect their valuable IP in the additive manufacturing field. The change in perception from additive manufacturing as primarily a tool for infringement to a tool that can be used to develop products and processes that are protectable means that inventors and innovators now have more scope to develop IP in the development of products made using additive manufacturing and in the manufacturing itself. As with any development, if it is a commercially valuable development, then IP protection should be sought to protect that value.

It can sometimes be difficult to assess whether a development is protectable or not. The patent attorneys at Wilson Gunn all have strong, practical experience in assisting inventors and innovators to identify and protect their IP.

If you have questions about additive manufacturing, new products or intellectual property in general, please get in touch to speak to one of our patent attorneys.